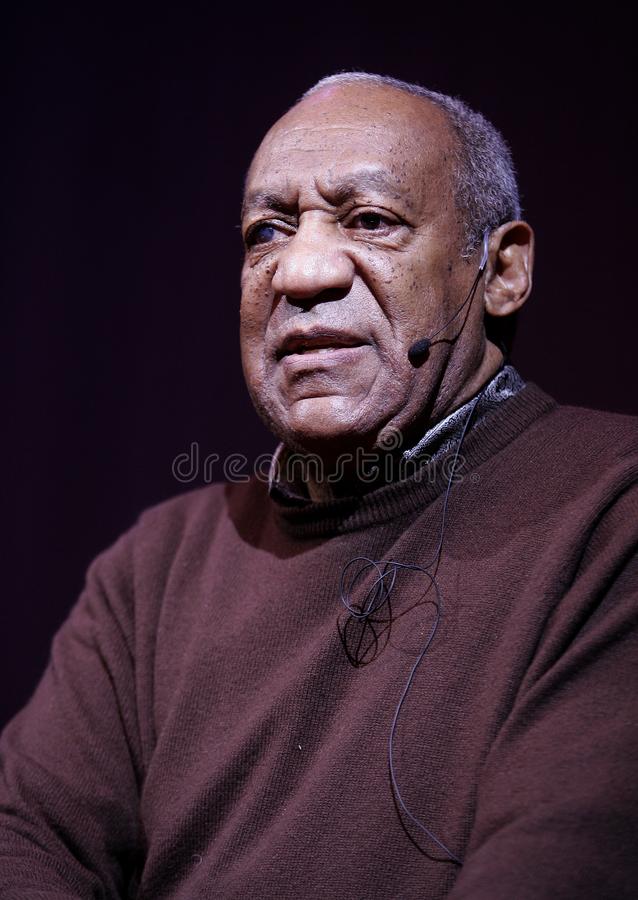

Not too long ago, I was looking for something that I ordered. I looked for that thing everywhere. You know that feeling. That feeling of knowing you have something, but not knowing where it is. The frustration. The flashes of mild anger and irritation. I realized this experience echoes one I’m having way too frequently, and that is the crushing disappointment when an artist whose work has deeply impacted you may not be the person you hoped they were. You need to know. But you don’t really want to know. So it is with Bill Cosby. One of the changes in my life mid-pandemic is the way I consume information. There was a time, before coronavirus hit, when I would research news stories to be fully versed on the subject matter (if I was interested in it). It appealed to the reporter in me, that nosy part of myself that loves learning every bit of the backstory. I’m not doing that all the time now because it is just too much. This pandemic has made me pull back from over-stimulation. But despite my mid-pandemic reluctance, there’s one rabbit hole I’ve avoided going down that I knew I needed to…the accusations of rape and now conviction of aggravated indecent assault by Bill Cosby. Le sigh.

I am one of those who grew up with Bill Cosby. I watched “Fat Albert” on Saturday morning with my brother. Our father took us to see every single one of his buddy movies with Sidney Poitier (which we watched so much we learned all the dialogue). As a little girl I heard his albums because older folks played them, and I watched him doing family friendly standup comedy on the night time talk shows long before they ended up in episodes of the iconic “The Cosby Show” of the late 1980s. For many of us who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, Bill Cosby was probably the most lauded Black man we saw on television who wasn’t an athlete. In fact, my own father slightly resembles Bill Cosby. They’re both chocolate brown, tall, witty, athletically built, funny, charming, nonthreatening in the way that made white folks comfortable, affable, and big on education. I’ve watched my father talk his way out of speeding tickets. Like Bill Cosby, people liked my dad…they wanted to like him and be his friend. We used to tease my dad that he was Bill Cosby without the money. Some of my younger cousins—the ones born in the 1980s—thought it was “Uncle Big John” they were seeing on tv on Thursday nights.

It’s been hard grappling with the allegations against Bill Cosby, but I knew at some point I would have to contend with them simply because his cultural presence was a fixture of my formative years. But those accusations. I needed to know. I started separating the man from his mythology after that “Pound Cake” speech. Turns out, “Heathcliff Huxtable” had an attitude. A judgmental one at that. Some of the mask was falling. I knew I would have to listen to the women who were accusing him of sexual assault. I needed to know if Bill Cosby was a predator not only because I held good feelings about him, his art, and his legacy, but because deep down I knew this many women would not be making these allegations if there wasn’t something there. Why did these accusations keep coming and going throughout his career if he wasn’t guilty? Or were we giving him the benefit of the doubt because he made us laugh? Because his son was murdered and our hearts broke for the Cosby family? Because of a default position that calls for us to protect Black men?

I’d heard allegations against him before stand-up comedian Hannibal Buress’ rant in 2014. I had heard Bill Cosby’s “Spanish Fly” bit; in fact, my aunties and older cousins used it as a warning to never to leave a drink unattended or accept a drink that you didn’t watch get poured yourself. Imagine my horror to find out from his accusers that he drugged them…by putting something in their drinks! Yet, Bill Cosby had so much favor that even that bit didn’t harm his persona as “America’s Dad.” But it was always there.

My first stop down the rabbit hole was listening to every single episode of the “Chasing Cosby” podcast by investigative journalist Nicole Egan. I wanted to hear from the women he harmed. Then I saw that one of my favorite thinkers, W. Kamau Bell, was directing a documentary entitled “We Need to Talk About Cosby” (It’s airing now on Showtime). I found a podcast he did with Larry Wilmore about the documentary and I listened to that too. W. Kamau Bell said something so profoundly accurate that I had to pause the podcast. He said part of the reason why rape/sexual assault is so pervasive is because we don’t live in a society that knows how to handle it. Now feminists have been expressing similar sentiments for decades. I’ve always known that there is a stifling amount of misogyny (contempt or ingrained prejudice against women) and misogynoir (misogyny that is directed against Black women where race and gender play significant roles in bias) in every social aspect of American life.

Sexual assault exists in our families, where we work, where we attend church. Our collective silence helps it thrive. This most certainly plays a role in how rape culture is cultivated, burrowing deeply into the social structures we occupy. In the film, “Promising Young Woman,” a frat boy bemoans that a man’s biggest fear is being accused of rape. A woman asks him if he can guess what a woman’s biggest fear is. The thought, apparently, had not even occurred to him. I remember the hype when the forever in reruns and soon to come back “Law and Order” tv show came out. It was promoted as a cop show that would feature ripped from the headlines cases dramatized for our entertainment. The inevitable spin-offs began, and since September 20, 1999, we’ve been watching Mariska Hargitay enter the cultural lexicon as Detective now Captain Olivia Benson tackle sex crimes in New York City in the Special Victims Unit. Twenty-three years of rape cases and they haven’t tapped out of material. This should horrify us. But it doesn’t. We’re kinda numb to it.

As so it was with Cosby. We’ve gotten numb to allegations of sexual assault against rich, powerful men. But the part that should horrify us about Cosby is this: we can never be sure whether it was the DOZENS of women telling their stories that finally shone the spotlight on his crimes, or whether it was a male comic calling another man out on his hypocrisy—that a man accused of rape shouldn’t be telling young Black men to pull their pants up—that did it.

The expression of the Divine in the form of woman is sacred, and no less sacred than any other expression of God. We have got to form community in ways that do not run on value privileging hierarchies. We’ve got to recognize the misogyny implied when survivors of rape are blamed for the acts of their assailants. In the school dress codes that penalize girls wearing clothing that could ‘provoke male lust’ without also challenging boys to learn how to manage their sexual urges because an erect penis is not an emergency. To create a world where two Black men having a discussion about how misogyny disrupts society doesn’t make me pause my podcast.

I wish we had a place where we can go to reflect on our collective grief about Bill Cosby. Not because he doesn’t deserve every bit of the vitriol he’s getting. He does. I’m thinking of those for whom Cosby was a positive influence. For many, he was the quintessential surrogate father. Can we be both disgusted and uplifted by an artist? What can we do when we absolutely want to know how something happened, but are terrified to actually know it? Was it his access to power that corrupted him? Or was he corrupt all along? Can we talk about Bill Cosby in our places of worship? And if not, why not? We certainly should be. Rape is mentioned in the Bible. And it is a violent crime that has traumatized women, children and men since before Jesus was born. The Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN) says a human being—a fully fleshed expression of God—endures the physical, psychological, emotional and spiritual pain of sexual assault every 68 seconds.

These are difficult things to talk about. My own wrestling with Bill Cosby the man and Bill Cosby’s legacy was uncomfortable and painful. Whatever the answers are, we will only find them by asking the questions. By having the difficult conversations. May God give us the will and the strength to take those painful, awkward, uncomfortable steps.