It is no secret that at one point, Black sororities and fraternities used “The Paper Bag Test” in order to screen pledges. But did you know some Black churches used it too? A lot of early Black churches were known to discriminate along the color line using the infamous “paper bag” and “comb” tests to screen potential members. The “paper bag” test consisted of placing your arm inside a brown paper bag; your arm had to be lighter than the paper bag to gain entry into the church. The “comb” test gauged the coarseness of your hair; if you could not run a comb through your hair from root to end, you were also denied entry. When W.E.B. DuBois declared “the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line,” he was not kidding. I don’t think he was solely referring to segregation either; it could easily be inferred that he was also referring to the color caste system that makes darkness was a problem.

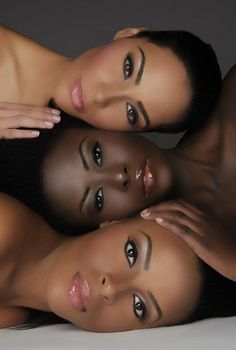

This color caste system, or color prejudice, refers to the privileging of the lightest skin tones over the darker and darkest skin tones. Other cultures have their own versions of the color caste system; India, Japan and South America all have varying degrees of what social scientists refer to as ‘pigmentocracy.’ There are also class issues involved here as well: those with darker skin were thought of as (and often limited to) the working class, while the economically advantaged worked in the shade.

This type of class currency was also present during American slavery. Fairer-skinned slaves often worked inside the home of the slaveholder, while darker-skinned slaves were relegated to the fields. I think the impossible work day of the field slave is where we get the expression “working from can’t see in the morning to can’t see at night.” This practice of assigning unpaid work assignments according to skin tone harbored a resentment that lingers to this day. The reasons for this discrimination vary. Slave narratives cite various reasons, such as the lighter-skinned slaves were very often the slaveholders very own children, for example. But the perceived benefits of ‘working in the big house’ were that they ate better, did not have to work in the heat, and some were instructed in reading and music. There were few ‘perks’ associated with working in the fields, particularly when they had to contend with the stifling sun, received few breaks, and often had to contend a whip-happy overseer just waiting for a reason. With this type of dynamic, it becomes easy to see why slaveholders would tell their slaves that it was God’s will for them to be slaves, and that darkness with associated with sin. Frederick Douglass talked about the use of ‘the curse of Ham’ as a justification for slavery in his autobiography.

Ham was the second son of Noah. The so-called ‘curse of Ham’ claims that Ham was punished, presumably cursed with enslavement, for not turning away when covering his father’s nakedness; apparently Noah got turnt up au naturel. (Genesis 9:20-27). Bottom line, the curse of Ham is propaganda that attempts to explain slavery as God’s will. It has also been used to explain why dark-skinned people were the ones enslaved because this is (allegedly) where all of the different skin tones of the world came from. Of course, this theory neglects to explain that it was not Ham who was cursed, but Canaan, and that color itself is not mentioned anywhere in that text (a good read on this would be Black Biblical Studies: Biblical and Theological Issues on the Black Presence in the Bible by Charles B. Copher). Needless to say, the association of slavery with darkness and curses has persisted despite the debunking of the so-called curse of Ham.

There are other places in the Bible that have been used to justify American slavery, such as the obedient slave admonitions in Ephesians 6:5; Colossians 3:22; and 1 Peter 2:18. When you include the tendency of the writers of the New Testament, particularly the writers of the gospel and epistles of John, to use binary language that uses the imagery of lightness and darkness to talk about God, it becomes even more apparent how much the Bible has been used to establish darkness as a problem. But we do not have to embrace it in the manner in which it has been served. One thing we can do to thwart the ideals about darkness in the Bible is to keep in mind that not only were early English versions of the Bible translated from a European perspective, but that the transatlantic slave trade was in full swing at the time! This is significant because translating the Bible into English required making choices about meaning since biblical languages are ordered much differently than English. For example, many scholars of the Old Testament make the case that the rendering of Song of Solomon 1:5, “I am dark, but beautiful,” could have just as easily been translated “I am dark and beautiful.” Scholars also argue that when God uses this rhetoric question in Amos 9: 7-8, “Are you not like the Ethiopians to me, O people of Israel?” God is showing Israel validation by comparing them to the Ethiopians; something one could argue God might not do if dark skin was a curse.

“In the beginning when God created the heavens and the earth, the earth was a formless void and darkness covered the face of the deep, while a wind from God swept over the face of the waters. Then God said, ‘Let there be light;’ and there was light.”

In Genesis 1:1-3, one might be tempted to view darkness here as a negative. Although the earth was formless and ‘darkness covered the face of the deep,’ it could be understood that the earth was simply without God’s presence. The earth just was. But once God breathed upon it, the earth had vibrancy; it had hope, it had purpose. I believe this use of darkness in Genesis refers to a state of being without hope and purpose. Jesus echoes this when he said, “I am the light.” In other words, Jesus is the bringer of hope. Proponents of the social gospel seek to apply the teachings of Jesus to social problems. I believe color prejudice is a social problem, and it is not just Black women who suffer its sting. May we always remember that the face of God bears the colors of all of us, and begin to view color prejudice as an affront to the God we serve.

It is a bit ironic that even though some elements of the church have been harmful to women of color, the church can also be the one place where Black women can have covenantal space to talk about how we have been harmed by color prejudice. Where else can Black women gather to not only touch and agree about it, but speak about it with women who understand it? The church would be a great place to open a ministerial dialogue about color prejudice on the job, in our relationships, in our homes. I just finished reading “Getting to Happy,” Terry McMillan’s sequel to “Waiting to Exhale.” It reminded me how much Black women need each other in our own healing processes. The church is not perfect. We should disabuse ourselves of the notion that it ever will be. The church is not a place for perfect saints; rather, it is much more like an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting for recovering ‘sin-oholics.’ I think, flaws and all, the church can still a great place for Black women to gather and sprinkle some Black girl magic on our collective wounds. Together.